Rethinking the Java DTO

Originally posted on the Scott Logic blog

As part of Scott Logic's graduate training program, I spent 12 weeks working with the other grads on an internal project. One aspect stuck with me more than the rest - the style and structure of our DTOs. It was controversial during the project, and the subject of much debate, but I've really grown to like it. It's not *the one true solution to all problems*, but it's an interesting approach which integrates well with modern IDEs. Hopefully, the initial shock will pass and you'll like it too!

What is a DTO (Data Transfer Object)?

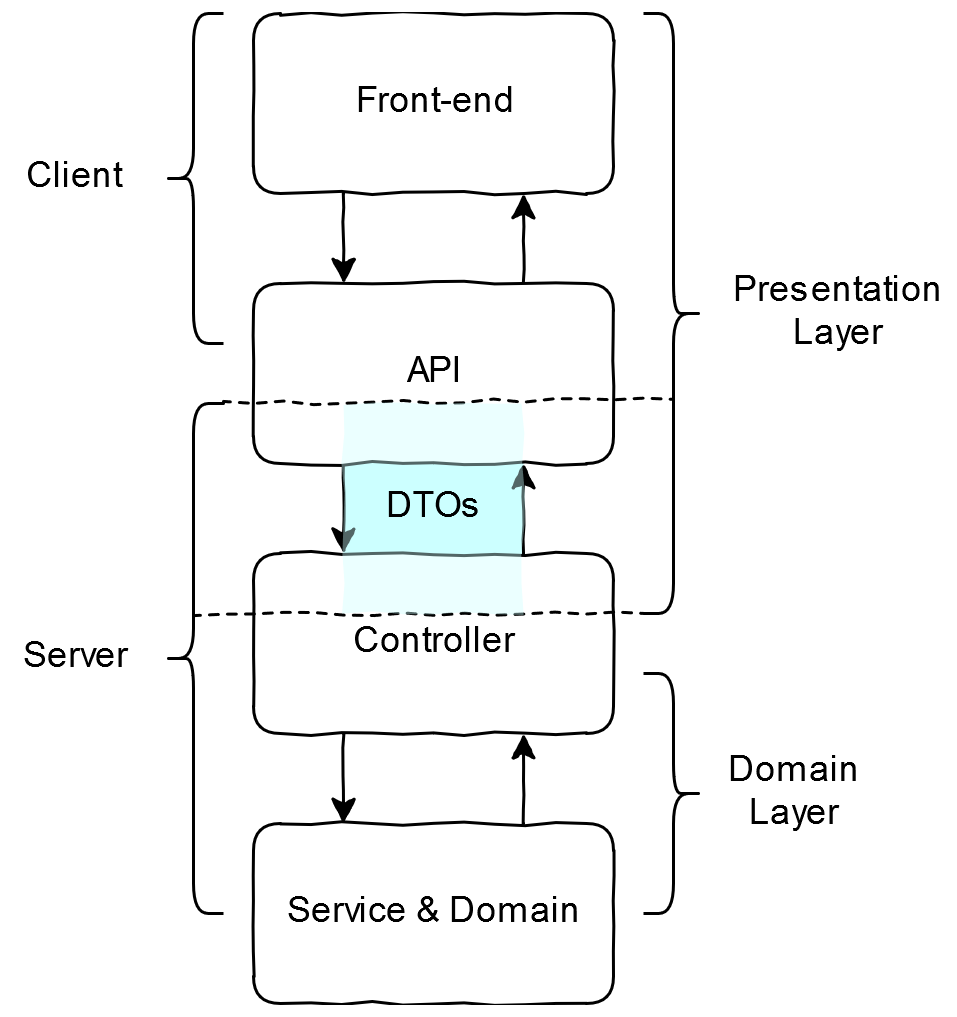

In client-server projects, data is often structured differently by the client (presentation layer) and the server (domain layer). This allows the server to store its information in a database-friendly or performant way, while providing a user-friendly representation for the client. The server needs a way to translate between the two data formats. Different architectures do exist, but we are just considering this one for simplicity. DTO-like objects can be used between any two data representations.

A DTO is a server-side value object which stores data using the presentation layer representation.

We separate DTOs into those received by the server (Request), and those returned by the server (Response).

They are automatically serialised/deserialised by Spring.

For context, here is an example endpoint using DTOs:

Endpoint

public class Controller {

// Getters, Constructors, Validation, and Documentation ommitted

public class CreateProductRequest {

private String name;

private Double price;

}

public class ProductResponse {

private Long id;

private String name;

private Double price;

}

public ResponseEntity<ProductResponse> createProduct(

CreateProductRequest request

) {

/*...*/

}

}

What makes a good DTO?

First, it's important to remember that you don't have to use DTOs. They are a programming pattern, and your code will work just fine without them.

- If you want to keep the same data representation in both layers, you can just use your entities as DTOs.

- If you want to manually serialise your entities into presentation layer JSON, I can't stop you!

They also document the presentation layer in a declarative human-readable way. I like DTOs, and think you should use them because they decouple the presentation layer and domain layer, allowing you to be more flexible while reducing the maintenance load.

However, not all DTOs are good DTOs. A good DTO should encourage API best practices and clean code principles.

They should allow developers to write APIs that are internally consistent.

Knowledge about a parameter on one endpoint should apply to parameters with the same name on all related endpoints.

For example, given the snippet above, if the request's price includes VAT then the response's price should include it too.

A consistent API prevents bugs that would be caused by differences between endpoints, while facilitating the learning of developers new to a project.

They should minimise boilerplate, and be fool-proof to write. If it is easy to make a mistake when writing a DTO, you will struggle to be consistent. DTOs should also be readable - we have this amazing description of the presentation layer's data representation, but it's useless if our DTOs are illegible. They should allow you to quickly view the data structure, even from another class.

Let's have a look at our DTOs before seeing whether they achieve those goals.

Show us the code!

This code will be confusing at first, but stick with it. Under the code, I describe how it all fits together. In the remainder of the post, I explain why we implemented it this way, and what the benefits are. Hopefully you'll understand the code and appreciate it by the end!

It is based roughly on actual code we wrote in our grad project, translated into the context of an online store. For each product, we store the name, sale price, and wholesale cost of its products. Prices are stored as floating-point numbers for the purposes of this example, but in real projects should be stored as BigDecimal.

ProductDTO

public enum ProductDTO {

;

private interface Id {

Long getId();

}

private interface Name {

String getName();

}

private interface Price {

Double getPrice();

}

private interface Cost {

Double getCost();

}

public enum Request {

;

public static class Create implements Name, Price, Cost {

String name;

Double price;

Double cost;

}

}

public enum Response {

;

public static class Public implements Id, Name, Price {

Long id;

String name;

Double price;

}

public static class Private implements Id, Name, Price, Cost {

Long id;

String name;

Double price;

Double cost;

}

}

}

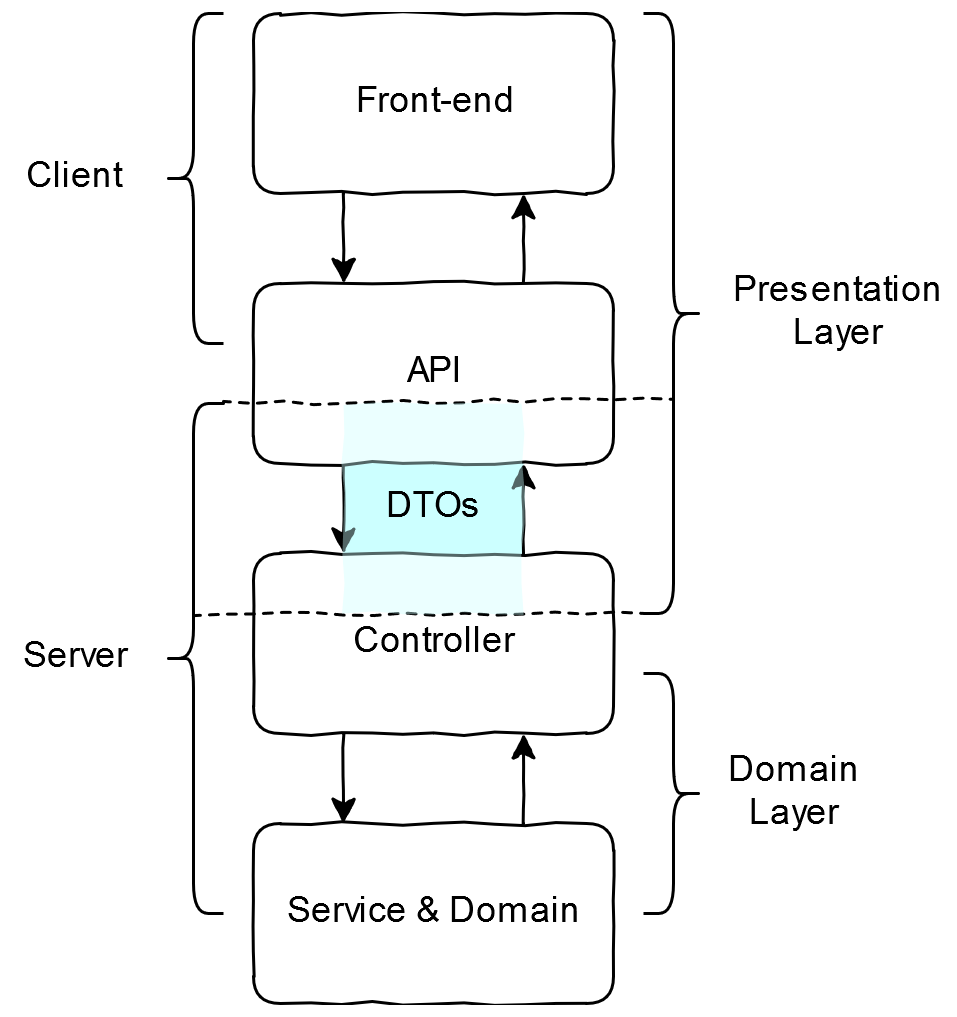

We create one file for each controller.

It contains a top-level enum with no values, in this case ProductDTO.

Under that, we split into Request and Response.

We create one Request DTO per controller endpoint, and as many Response DTOs as necessary.

In this case, we have two Response DTOs, where Public is safe to send to any user and Private includes the wholesale cost of a product.

For each API parameter, we create an interface with the same name as the parameter. Each defines a single method - the getter for that parameter. Any validation goes on the interface's method - for example, the `@NotBlank` annotation ensures that no DTO will ever have `""` as its name.

For each field on a DTO, we implement the associated interface.

Lombok's @Value annotation auto-generates getters which satisfy the interfaces.

For a full comparison with documentation, see the two examples: before and after. Bear in mind that this is a small example, and the differences become more apparent as you add more DTOs.

"I hate it"

It is really weird. There's a lot of unusual things going on there - let's discuss a few in detail.

There's three enums and none have any values!

This is a trick to create namespaces in java, meaning we can reference a DTO as `ProductDTO.Request.Create`.

That trick is also the reason there's a trailing ; after each enum.

The semicolon indicates the end of the (empty) list of values!

Using namespaces improves discoverability by allowing us to type ProductDTO and rely on auto-completion to list the DTOs.

There are other ways of achieving that, but this way is very concise, while preventing new ProductDTO() and new Create().

Honestly, this is personal preference and you can organise the classes however you like.

There are also a lot of interfaces - one per API parameter! This is because we use the interfaces as a single source of truth for that parameter. I will talk a lot more about this later - but trust me that it brings a lot of benefits.

The interface methods never get implemented! Yeah, this one is pretty weird and I wish there was a better way. Using Lombok's auto-generated getters to implement the interface is quite hacky. It would be much nicer to just define fields on the interfaces, which would also mean the DTO classes could be one-line long. However, java doesn't allow interfaces to have non-static fields. If you followed this pattern in other languages, it would be much neater.

It's (almost) perfect

Let's go back to the list of things that make a good DTO. Does this style achieve those goals?

Consistent Syntax

We definitely enforce consistent syntax - and that was the main reason we started using this pattern. Each API parameter has its syntax defined by the associated interface. If the DTO class contains a typo in a parameter name or incorrect return type, the code won't compile and your IDE will warn you. For example:

SyntaxError

public static class PatchPrice implements Id, Price {

String id; // Should be Long id;

Double prise; // Should be Double price;

// PatchPrice is not abstract and does not override abstract method getId() in Id

// PatchPrice is not abstract and does not override abstract method getPrice() in Price

}

Additionally, since validation is placed on the interfaces, it is consistent between DTOs. You can never have a situation where a value can be valid for a parameter on one endpoint but not another.

Consistent Semantics

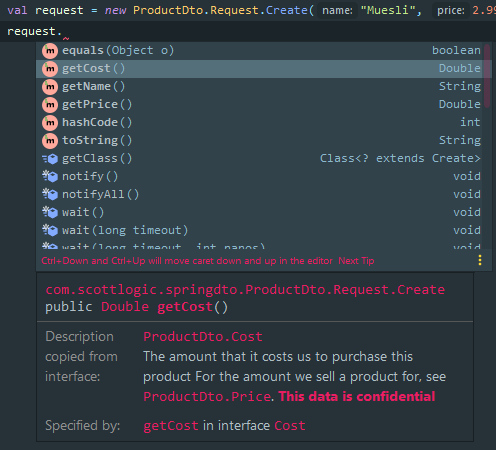

This style helps enforce consistent semantics through inherited documentation. Each parameter has its semantic meaning defined by the documentation on associated interface method. For example:

Semantics

private interface Cost {

/**

* The amount that it costs us to purchase this product

* For the amount we sell a product for, see the {@link Price Price} parameter.

* <b>This data is confidential</b>

*/

Double getCost();

}

Since the DTO classes implement the interfaces, the documentation is automatically inherited by the getters. This means that on every DTO instance, you can learn the semantic meaning and validation rules for a field by viewing the documentation for the method:

You're also guaranteed that this documentation is present and consistent across all DTOs that implement a given interface. In the rare case where an API parameter with the same name *should* have different semantics, this style enforces that a new interface should be created. While this is a hassle, it forces the developer to stop and think, while also allowing future readers to immediately see that something is different.

Readable & Maintainable

There's no getting around this - our style introduces a lot of boilerplate.

There are four interfaces that could be removed, and each DTO class has a long implements list that doesn't need to be there.

However, the interfaces can be hidden away in their own package, which helps maintain the signal:noise ratio of the actual DTO class.

Still, the boilerplate is the main downside of this style, and it's reasonable to choose a different style on that basis.

To me, it's worth the extra interface definitions.

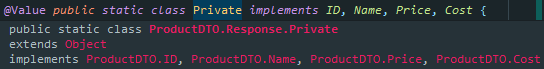

Our style really shines when it comes to creating a new DTO.

You simply write @Value public static class [name] implements, followed by a list of the fields you want.

Then, declare the fields demanded by your IDE until it stops complaining.

You're done - a full DTO with validation!

Additionally, it's trivial to see the structure of our DTO classes.

Looking at the code, you can see everything you need from the class signature.

Each field is listed in the implements list.

Since it's all declared in the class signature, you can simply press `ctrl+q` in IntelliJ and see the list of fields.

Our style has write-once validation, as all validation is added to the interface methods. When writing a DTO, you get validation for free after implementing the interface.

Finally, thanks to our single-method interfaces, we can write reusable utility methods. For example, given the sale price and wholesale cost of a product, we can calculate its markup:

markup = (sale_price - cost_price) / cost_price

In Java, we can implement this using a generic method with type parameter T:

Generic Types

public class GenericExample {

public static <T extends Price & Cost> Double getMarkup(T dto) {

return (dto.getPrice() - dto.getCost()) / dto.getCost();

}

}

Our single parameter has type T, which is a generic intersection type.

dto must implement both Price and Cost - meaning you can't pass a Public response to getMarkup (as it does not implement Cost).

With normal DTO classes, we would have to write this as a method which takes two parameters, adding overloads for each DTO (see the example).

This offloads the work onto the caller, and risks getting the parameters backwards, causing bugs.

Conclusion

I don't expect you to go away and rewrite all your DTOs right now. There are, however, a lot of small things you can take away:

- Establish a single source of truth for your API parameters

- Small interfaces are better

- Try being weird, maybe you'll like it!